Soseki's Life

Childhood

Natsume Soseki (whose autonym was Natsume Kinnosuke) was born February 9, 1867 in Ushigome-babashita-yokocho, Edo (now, 1, Kikui-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo). He began his life as the youngest son of Natsume Kobee Naokatsu, his father, and Natsume Chie, his mother.

He was named "Kinnosuke" because his birthday was, according to the Chinese sexagenary cycle, "57th sexagenary cycle day. The children who were born on the 57th sexagenary cycle day were believed to be thieves, but there was a superstition that in order to avoid that doom you must use the chinese character "ķćüE (which means "gold" and pronounces /kin/) when you name your child" (Natsume Soseki written by Komiya Toyotaka).

Soon after he was born, Soseki was out at nurse and fostered. He recalled his situation of the day as follows:

I was born to my mother late in her life. Although she is already dead, I still hear someone say her story that when she bore me she felt ashamed because she was too old to have a child. For this and some other reasons, soon after I was born my parents asked someone to foster me and sent me there. Of course I do not remember who fostered me, but after I came of age I heard that I was fostered by the couple, who made a living running a used goods shop.

("Inside My Glass Doors")

He returned to his birthplace once, but was soon adopted by the couple of Shiobara Shonosuke and Yasuko, who was the rich farmers around Daishu-ji at Yotsuya.

I don't remember when I returned to my birthplace. Yet, I was sent to be adopted by another couple. I am not sure but I was adopted when I was 4 years old. I was brought up there until the age of eight or nine, but as my foster father and mother got divorced I again returned to my own family.

("Inside My Glass Doors")

Grass on the Wayside, the autobiographical novel, describes the relationship between Kenzo, the hero considered to be based on Soseki himself, and Mr. and Mrs. Shimada, who are considered to be the counterparts of his foster parents.

At such cold nights that they sat around the hibachi, Kenzo was often asked some questions like this.

"Who is your father?"

Kenzo looked at Mr. Shimada and pointed to him.

"Then, who is your mother?"

Kenzo looked at Otsune[Mrs. Shimada] and pointed to her.

They were satisfied with his answer and then asked the similar question in other way.

"Then, who are your real parents?"

All he could do was to make the same reluctant answer again.

[...]

In some times, they repeated this dialogue almost every day. In other times, Mr. and Mrs. Shimada made further inquiry. Particulary Otsune was persistent.

"Where are you born?"

üEüEi>Grass on the WaysideüEüE/b>

In 1875 his foster parents got divorced, and he returned to his own family as the adoptee of Mr. and Mrs. Shiobara. He legally became the child of Natsume family again in 1888.

Soseki began to have the aspiration for literature when he was 15 or 16 years old.

I also read the Chinese books and novels, and was interested in literature. I wanted to be a novelist and told my ambition to my late brother. He scolded me, saying that I could not make a living as a novelist and that writing novels is only an "accomplishment". After considerable reflections, I concluded that I wanted to get the job which I was interested in, and that at the same time it should be needed by the society.

("Conversation (The time was with me: Jiki ga kite itanda)") in Japanese

School Days

Soseki's Meeting and Exchange with Shiki Masaoka

In September of 1884, Soseki entered the Tokyo Daigaku Yobimon(University Preparatory School). Among his classmates were: Tsunenori Masaoka (whose pseudonym is Shiki Masaoka and who later became a haiku poet), Kumagusu Minakata (who became a scholar), Butaro Yamada (who later became a novelist and whose pseudonym was Bimyo Yamada), Yaichi Haga (who also became a scholar of Japanese literature).

Soseki and Shiki later literarily influenced each other, but at that time they did not seem to commune with each other.

Shiki Masaoka (whose autonym was Tsunenori, and whose childhood name was Tokoronosuke and later changed into Noboru) was born on 17th September 1867 in Fujiwarashin-Cho, Onsen-Gun, Iyono-Kuni (now, Hanazonomachi, Matsuyama City). His father was Tsunenari, who was a samurai and worked for the fief of Matsuyama domain. His mother was Yae, who was the eldest daughter of Kanzan Ohara (who was the confucist working for the fief of Matsuyama domain). As his father died young, Shiki, Ritsu his sister, and his mother was supported by Ohara family. Particulary his grandfather Kanzan cherished Shiki, teaching how to pronounce chinese characters in order to read aloud Chinese classics without understanding (to read aloud witout understanding is Japanese Confucists' basic way of training). Shiki adored his grandfather so much that he later wrote "At that time I wanted to be a scholar, close equivalent of my grandfather" (Fude-makase (writing without thought)). His mother Yae recalled his childhood, saying "when he was young, he was very coward. [...] As he came back home being bullied by his classmates, his sister threw stones, revenging herself on them in place of him. Such a cowardice he was."("Bodo-no-danwa" (Mother's conversation))

Shiki himself wrote "When I was young, I was called cowardice and crybaby. Even after I went to the elementary school, I was often bullied and cried."(Bokuju-itteki(a drop of Chinese ink))

Shiki was absorbed in compositions. It was said that he wrote magazines and had them circulated. When he enter junior high school, he showed keen interest in politics and gave many political addresses.

Around 1882 Shiki hoped to study in Tokyo, and on June 1883 his desire was satisfied: he went to Tokyo. He wrote in Fude-makase, "There are three happiest occasions in my life: First, the time when my uncle in Tokyo sent me the letter that he let me stay in his house."

In 1885, Shiki failed the test in the end of his first academic year and could not move up into the second grade. "When I took the Math test, there was a rule that the answers had to be written in English" and thus "I had to deal with the two difficulties at the same time: Math and English." "I could not pass the examination, not becuase I failed the geometry test but rather the English test." (Bokuju-itteki(a drop of Chinese ink))

Talking about Soseki, he "very much liked to be lazy and did not study at all" and he "thought that although he did not study, he was proud of himself" ("Rakudai" (means failure in English)). In 1886, he suffered from peritonitis and could not take the senior examination. Needless to say, he did not do well in the university. Thus, he could not go on to the next grade. Later, he wrote about this failure:

Now I feel somehow strange, but if one studies seriously he can clearly understand what he have not understood at all. [...] In such a way I changed my mind and was engaged in studying after the failure. The failure seems to me an awful-taste but powerful medicine.

("Rakudai" (means failure in English))

On September 1888, Soseki and Shiki entered 1st Junior Higher Scholl (Humanity). At first Soseki intended to be an architect. He chose the department of architecture thinking that he wanted to build a pyramid, but his classmate Yasusaburo Yoneyama encouraged him to do the literature, saying that "You should rather do the literature. If you study hard, it is not impossible that you can build the novels that stand as long as the pyramids." This is why he "changed his mind and enter the department of literature." Yet, as he "did not find it necessary to study Japanese literature and Chinese classics," he "chose to be major in English literature" ("Rakudai" (means failure in English)).

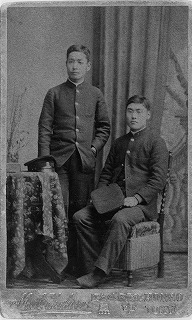

Left: Soseki in his schooldays, Right: Yasusaburo Yoneyama

According to Soseki, Yoneyama was "a really strange person and always telling something big such as about universe and life" ("Conversation (The time was with me: Jiki ga kite itanda)") and Yoneyama was familiar with Shiki. It is said that one reason why Shiki changed his major from philosophy into Japanese Literature was because he was surprised at Yoneyama's ability and thought that he could not be equal to Yoneyama.

Soseki and Shiki were on freindly terms around January 1889. Their bond became closer and closer through their shared hobby such as yose, where people went to enjoy the Japanese comic storytelling. Shiki called Souseki in Fude-makase "very close friend" and "his respected friend"

Later year, Soseki recollected Shiki:

Shiki was very fastidious and was rarely associating with anyone except me. [...] One reason why he and I came to friendly terms with each other was that when we two talked about yose he was proud of himself thinking that he knew lots about yose. Yet, to his surprise I also knew lots about yose, so I think that he found his equivalent. Since then, he came close to me. [...]

Shiki wanted to be in charge of everything. When we were walking together he used to decide where to go and lead me. This might be because I was idle and I always followed his decisions.

("Masaoka Shiki")

Shiki behaved as if he were a teacher of mine. When he read my haikus he immediately corrected them or highlighted good expressions. I could accept his treatment [as Shiki taught Soseki how to compose haikus], but when I wrote Chinese poems he also corrected them or highlighted good expressions, and then gave them back to me. So I wrote English composition and had him read and correct it, but as he did not understand it he wrote down on it "Very good" and gave it back.

(Soseki-shi to watashi (means Soseki and I in English) written by Kyoshi Takahama)

On the other hand, Shiki wrote:

I both like companionship and do not like companionship. I like companionship because I want to have good friends, talk about each other's ideas, feelings, and affairs, and help each other in the face of hardships. I do not like companionship because I want to avoid bad friends, not wanting to waste time with them and on the temptations they gave me. I was eccentric and stubborn. Some people I love recklessly while other people I dilike very much.

(Fude-makase of 1889)

Soseki is the most serious. In school he strictly teach his students and never let students corrupt the school discipline.

(Bokuju-itteki)

Soseki's disciple Torahiko Terada recall Soseki and Shiki as follows:

The topic moved from Soseki's situation in Kumamoto to the rumors about master Soseki, and I hear the stories about their school days. When he was in his school days, master Soseki was calm and docile and seldom absent from the university. On the other hand, after Shiki began to classify the haikus he often absent from the university. Master Soseki and Shiki got close friends four years after they first met. Once they came to friendly terms, they discussed childishly and sometimes quarrelled.

("Shiki-an wo tazunau ki" (the record of visiting Shiki's house))

When I graduated from the higher school and entered the universty, I got my master's letter of introduction and visted Masaoka on his sickbed at Uguisu-yokocho, Kami-negishi. At that time, Shiki told me that he took pains to offer master Soseki the employment. In fact, I think that Shiki and the master respected each other and that they are the closest friends to each other. Yet, when I asked master Soseki about Shiki, he sometimes answered "Mr. Masaoka thought that he was greater than I. He was presumptuous" and laughed. Although he answered like this, I found that he and Shiki were congenial friends.

("Natsume Soseki Sensei no tsuioku" (means in English my remniscent of my master Soseki Natsume))

On early May 1889, Shiki vomited blood and was diagnosed as tuberculosis. At this time, Shiki composed dozens of haikus about the Eurasian little cuckoo such as "U-no-hana wo/ megakete-kitaka/ hototogisu" and "U-no-hana no/ chiru-made nakuka/ hototogisu", and since then he called himself "Shiki" (which is the Chinese name of an Eurasian little cuckoo). The Eurasian little cuckoos are said to be "singing and vomiting blood", and thus the Eurasian little cuckoos are the images of tuberculosis. Shiki expected his remaining life to be "ten years" ("Kakketsu-shimatsu" (the whole story of my vomiting blood)). Soseki, on 13 May 1889, sent the letter that showed his worry concering Shiki saying "As you are in a serious condition, you must keep in mind that all you have to do is to rest" and "Please do take care of yourself for your mother and Japan". To the letter he attached the two haikus: "Kaerou to/ nakazuni warahe/ hototogisu" and "Kikahu-tote/ daremo matanuni/ hototogisu". As Soseki's two elder brother died of tuberculosis and at that time one of his two remaining brothers was suffering from tuberculosis, he had to be particularly worried about Shiki. Shiki's sickness made their relationship closer.

On late May, Soseki wrote the criticism of Shiki's Japanese and Chinese poem collection Nana kusa shu (the collection of various poems) in the end of that collection, where for the first time he called himself "Soseki". Strangely, the pseudonym "Soseki" was used also by Shiki around 1891-2 (Fude-makase).

On the other hand, Shiki read Soseki's travelogue Boku setsu roku written in the style of Chinese poems and sent Soseki "the afterword for the travelogue" although Soseki "did not ask him to write it" ("Masaoka Shiki"). There Shiki extolled the travelogue, writing "Soseki is the greatest genius Japan has ever had in this ten thousand year".

My experience teaches me that people have both merits and demerits. For example, people who are good at English and Western science are poor at Chinese Classics and its knowledge. On the other hand, people who are good at Japanese classics and its knowledge are poor at Math. Only Soseki is good at everything and reaches the depths of everything. People know that he understands English and Western Science very well, but do not know that he fluently writes classical Chinese and its poems. Thus, I specially mention it.

(Fude-makase)

Inspired by Shiki's Nana kusa syu, Soseki wrote Boku setsu roku, which was written above all "in order for Shiki Masaoka to read it" ("Commentary on Boku setsu roku" written by Toyotaka Komiya).

Thus, the relationship between the sworn friends Soseki and Shiki, who have promising literary skills, begins. As Soseki wrote "Mr. Masaoka sent me letters indiscriminately and I also sent the same amount of the letters" ("Masaoka Shiki"), their relationship became closer through the letters, too. For example, Soseki wrote his anguished feelings openly to Shiki "I recently somehow dislike involvements with people and society" and "I am ashamed to confess this to you but this I am forced to do because of my misanthropy" (on 9 August 1890). In other times they sent the letter criticizing candidly each other over their own view of literature and life.

Do you begin to write the novel you have cherished? What kind of style will you intend to use? I will read it and try to make detailed comments, but your sentences are very ladylike.

(The letter to Shiki on 31 December 1889)

I believe that you are particulary discerning among my friends. You have definite view and decide to lead your life. I cannot believe that such a friend as you gave me this flimsy booklet and told me to imitate it. I do not understand your intention.

(The letter to Shiki 7 November 1891)

In another times, the two enjoy calling each other "mistress" and "husband" (The letter to Shiki on 27 September 1889). Soseki wrote Shiki the letter that seemed to allude his love to a woman: "By the way, I went to the oculist yesterday. I saw the pretty woman I told you before, whose hairstyle was icho-gaeshi, an old woman hairstyle, and who wore takenaha, an old comb. I do not anticipate it, so my face reddened" (The letter to Shiki on 18 July 1891)

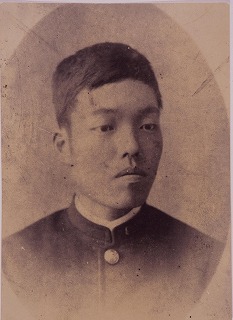

Shiki in school days (1890)

On September 1890, Soseki entered the Department of English Literature at the Tokyo Imperial University, and Shiki the Department of Philosophy (later he changed his major into the Department of Japanese Literature).

The Department of English was newly-organized in 1890, and there was only two students in the department including him, and the other student was two years senior to Soseki. The new-comer in 1890 was only Soseki himself. Among the students 3 years junior to him was Bansui Doi, who later became a famous poet and a famous student of English Literature.

He was taught English Linguistics and Literature by Prof. Dickson. Soseki was an excellent student and Prof. Dickson asked him to translate Hojoki into English. He attended the lecture of Raphael von Koeber in 1893.

Soseki got a scholarship, but he had obscure worries and doubts about what he should do as a student of English Literature:

I majored in English Literature in the university. You may ask me what the English Literature is, but I, who spent 3 years on studying it, cannot understand what it is. At that time, my teacher was Prof. Dickson. I was made to read the poetry or the sentences in front of him and also write compositions, and then was scolded by him for omitting articles or mispronouncing the words. When I took the tests, I was asked such questions as: "When was William Wordsworth born and dead?", "How many are the versions of Shakespearian Folio?", or "Arrange the works of Sir Walter Scott in chronological order". The young students such as you can imagine my doubt: is this the study of English Literature? Apart from the English Literature, this way of learning does not enable us to understand above all what literature is. [...] Anyway, I spent 3 year studying English Literature, but I did not understand what the Literature is. [...] I, who had such a vague idea of Literature, was forced to be a teacher regardless of my will. As for English as the language, I managed to give lectures and thus each day passed without arousing any particular anxieties or doubts. Yet, I always felt empty. No. I rather wanted to feel so, but I could not endure my situation sensing that wherever I went I faced something disgusting and obscure.

("Watashi no kojin-shugi" (means in English my individualism))

Soseki became a lecturer of Tokyo Senmon GakkoüEüEresent Waseda UniversityüEēin 1892, and in 1893 he became a part-time lecturer of Tokyo Higher Normal School. Yet, in 1893 he suffered nervous breakdown so much that in December he visited Engaku-ji at Kamakura and practiced meditation in Zen Buddhism.

On the other hand, Shiki was interested more in haikus and novels than the study in the university.

He was "haunted by the devil of haikus" to the degree that the more attentions he "paid to studying instead of haikus preparing for the test" the more he "thought of haikus". He "felt that he could not avoid that devil" (Bokuju-itteki). Thus, he gave up studying and failed the test at the end of 1892. On the end of the March 1893 he dropped out. Soseki wrote him a letter and asked him to think better of the dropout, stating "although the study in the university seems silly to you, you should graduate from the university. Please think better of dropping out" with the haiku "naku naraba/ mangetsu ni nake/ hototogisu" (The letter to Shiki on 19 July 1892). Yet, Shiki dropped out and chose to live his own life.

Shiki, on December 1892, entered Nippon Shinbun-sha, whose employer was Katsunan Kuga. He was already writing several serials in "Nippon": "Kakehashi no ki", "Dassai Shooku Haiwa", and so on. After he entered the company, he made a column of haikus in "Nippon", innovating haikus.

Shiki, although he was sick, went to China as the Shino-Japanese War correspondent on 10 April 1895. There he met Ogai Mori and talked about haikus. Yet, this service in the war made his condition worse and worse.

At the same time, Soseki went to Shiki's hometown Matsuyama as an English teacher.

Matsuyama and Kumamoto Era

Matsuyama Era

On April 1895, Soseki's friend Torao Suga recommended Soseki to old-system middle school in Ehime prefecture, and Soseki left for there as an English teacher. Soseki's salary was higer than that of the principal: 80 yen a month, an exceptionally good treatment. He used Matsuyama as the stage for Botchan.

After I graduated from the university, for a while I worked for (old-system) middle school at Matsuyama in Iyo [now Ehime prefecture]. The students I taught there were the models for the fellows who spoke the Iyo dialect in Botchan. I did not behave like the Botchan, but there was such a spa as I wrote. Moreover, there is a teacher at Matsuyama Middle School, who people think is the very likeness of Yamaarashi(Porcupine). People say that I made the character based on him, but I was amazed since I did not modelled the character on him.

("Conversation: My old time")

However, Soseki doubted about his aptitude for the teacher.

I am not suitable for a teacher because I do not have the endowments required for the job. I am the unsuitable person. The job I could get most easily is the teacher. This shows the sad facts that there are no true educators in Japan and at the same time that the students in these days can be taught by the false teachers without any complaints.

("Guken susoku" in Japanese)

Soon, Shiki, who went to China as the Shino-Japanese War correspondent, returned to Japan. Yet, he vomited blood again on his way to Japan, and in order to rest he went back to his hometown Matsuyama. Soseki, for about 50 days until Shiki went to Tokyo, Soseki let Shiki on his bed to stay on the first floor and he live on the second floor.

Soseki wrote to him "I recently want to join the group of haiku poets, so when you are free please teach me how to make them" (The letter to Shiki on 26 May 1895), and called himself "Gudabutsu" [the modest Amida] and joind Shiki's party of haiku friends. After Shiki went to Tokyo, Soseki sent his haikus to Shiki and asked Shiki's remarks.

I was on the second floor and he [Shiki] the first. Shortly, Shiki's disciples, who were students of Matsuyama Middle School, gathered and Shiki taught them how to write haikus. When I came back, a lot of them was there, loudly discussing haikus. I could not read books because of loudness. I did not have any spare time to read, though I did not read many books from the first. As I did not have anything else to do, I did not want to but wrote haikus. In addition, he had a broiled eel delivered at lunch time and as you already know he ate it making unpleasant sounds. He ordered and ate the eel without consulting me.

("Masaoka Shiki")

Shiki, in the middle of October of 1895, left Matsuyama. Shiki's most famous haiku "Kaki kueba/ kane ga naru nari/ horyu-ji" was composed in Nara, where he visited on his way to Tokyo.

In December of 1895, Soseki was arranged to meet Kyoko Nakane (usually called Kyo and her registered given name was Kiyo) and contract a marriage with her. Her father Junchi Nakane was the head secretary of House of Peers and she was his first daughter. Soseki gave his impression on her to the people around: "Her teeth are irregular and yellow, but she did not care to hide them. I like her openness" (Soseki no omoide (my memory for Soseki) written by Kyoko Natsume). Soseki, who went to Tokyo in order to meet her, on 3 January 1896 join the haiku party at Shiki's house (Shiki called his house Shiki-an [,the Shiki's hermitage]). In this party joined Shiki, Soseki, Kyoshi Takahama, Hekigoto Kawahigashi, Ogai Mori, and so on.

Kumamoto Era

On April 1896, Soseki was tranfered to 5th Higher School in Kumamoto. On June, at his leasehold the wedding ceremony was conducted. Soseki, in his letter to Shiki on 10 June 1896, composed the haiku: "Kinu kae te/ kyo yori yome wo/ morai keri". In celebration of Soseki's marriage Shiki wrote the following haiku: "Shinshin taru / momo no wakaba ya/ kimi metoru".

Soon after Soseki and Kyoko got married, he said to her, "As I am a scholar, I must concentrate on studying. I do not have any spare time to care about you. You must understand that"

(Kyoko Natsume op. cit.).

On the other hand, Shiki was suffered from the spinal caries and was on bed around 1896. In 1897, for his spinal caries two operations were carried out. When he was diagnosed as the spinal caries, Shiki wrote to Kyoshi Takahama "There cannot be a man as ambitous as I who was dying" (The letter on 17 May 1897). Yet, although he was on bed, he continued his composition.

In 1898, in the newspaper "Nippon" he wrote the serial of "Uta yomi ni atauru sho" (means in English the article for the tanka poets), embarking on innovating the tanka. In 1899, he published Haikai taiyo (means in English the summary of haikus) and Haijin Buson (means in English Buson as haiku poet), and on February 1900 announced "Joji bun" (literally means in English descriptive sentences), advocating the notion of shasei bun (which can be paraphrased sentences sketching something or someone). Syasei bun were inspired by the western theory of sketch, which his close friend the western painter Nakamura Fusetsu told him. Shiki explains: "when seeing the intersting scenery or the human events and wanting to arouse the same interests in readers as in us by changing them into sentences, we must not decorate and exaggerate the sentences but describe things just as they are" ("Joji bun")

Shiki wrote the long letter dated on 12 February 1900 to Soseki, which began "This letter is about my usual complaints, so please read it when you are free". In the letter, Shiki asked Soseki never to "let others read this letter".

As I am writing about shedding tears, perhaps you will worry about me. The reason is: when you visited Dr. Suda, I went with you and was also examined. At that time, I asked the doctor "what disease I am suffering" and he answered jokingly "your lachrymal glands are closed". I did't care about his remark, but when now I think of it it is an intersting disease. Not because of this diagnosis, at that time I did not cry much. Once, needless to say after vomiting the blood, I faced something sad and said to you "Yesterday I cry", and you said "Tears from hardest heart" and laughed. Since after I entered the Kobe hospital, I have had the tendency to cry. Recently I cry more and more times. Something not worth crying for can make me cry. When I felt something mysterious I immediately began to shed tears. [...] When I am wondering whether in this summer you come to Tokyo and visit me, I begin to cry. Not because I sense that I do not meet you anymore. Yet, you do not have to worry. Needless to say, actually meeting with you cannot make me cry. When I fancy I cannot help crying. [...] Among my friends I think you are the only person to receive my complaints and then laugh. For this reason I choose you to tell my complaints, so do laugh at me. When I am thinking of it when not crying, it is very funny. ............Yet, you don't take this letter seriously and answer. [...] If you and I sit facing each other and you tell me to put a stove in my room, I will just answer "yes" and I will not cry at all. However, if you send me a letter telling me such a thing I will cry a bit. I will not shed a tear as soon as I read your letter. Yet, when I am on bed and think of the letter, I sometimes cry. As I cry when I physically weak, I am much like old people chanting a prayer to Buddha and shedding tears. So don't reply to this letter. I am satisfied if you read this letter and laugh. [...]

If I complain about another thing, I will tell you. Yet, as I am now satisfied after I tell you my complaint, here I stop complaining. I want to write my thanks for the kumquats you sent me, but instead I write about my complaints. Don't let others read this letter. In case someone read this letter I have it registered.

Shiki, on 3 May, presented Soseki's first daughter Fudeko with three Hina-ningyos (the dolls dressed in old-style kimonos representative of the people in the court). These were "the shabby and ordinary San-nin kanjo (the 3 dolls representative of the court ladies)". Yet, "the smallness and shabiness of the dolls remind me of his life. Thus, I [Soseki] want to meet him and appreciate his kindness" ("Shiki's Hina" written by Yuzuru Matsuoka)

Moreover, in the middle of June Shiki sent Soseki the picture of "Azuma-giku" (the Japanese name of Aster savatieri Makino). Shiki, from around the autumn of 1889, by using the coloring Fusetsu Nakamura gave him began to make sketches. Shiki in his later years found comfort and pleasure in drawing sketches.

On "Azuma-giku" Shiki wrote down "Please suppose that this is the withered flower. The picture is poor because the sick person is drawing. If you think I am telling a lie, please try to draw a picture with your elbow on the floor". Soseki commented on Shiki's picture as follows: "This picture is an Azuma-giku in a bud vase." In order to draw "this very simple picutre" he "seemed to make great efforts". Soseki remarks that "this picture cannot hide his unskillfulness" ("Shiki's Picture").

Shiki's pictures, among which is "Azuma-giku", are poor and serious. His extraordinary literary talent cannot make up for his unskillfulness in drawing. I cannot help smiling. [...] Shiki as a person and as a writer was not honest at all but good at everything. During my exchange with him, I have never had the opportunity of laughing at his awkwardness or had the chance of being in love with his honesty. After 10 years have passed since he died, it makes me have a wry smile and arouses some intersts to find for the first time his awkwardness in this Azuma-giku. Yet, the picture makes me lonely. I wish that Shiki would draw this picture exaggerating his awkwardness and make up for this loneliness.

("Shiki's Picture")

Soseki, who was ordered to study in England by the Ministry of Education, visited Shiki on his sickbed with Torahiko Terada on 26 August 1900. This is the Soseki's last meeting with Shiki. Shiki wrote in Hototogisu v.3(12):

Soseki, who was ordered to study in England, in this summer left Kumamoto for Tokyo and after a long separation I met him. On 8 September he got on the German ship and left Yokohama for Europe. After I got seriously ill 3 years ago, every time I see off the people who was sailing to Europe I felt lonely because I felt that I could no longer meet them. Yet, many of those people returned to Japan and I met them again. However, as soon as I heard that Soseki was going to go to England I thought that this time I could not see him again and felt lonely.

Soseki stayed in Kumamoto for about 5 years. Among the students he taught is Torahiko Terada. It is said that the person who took pains to invite Kokichi Kano to 5th Higer School as the professor was Soseki. Soseki go out to Oama spa with Kano. His life in Kumamoto resulted in The Three-cornered World and The 210th day.

The Study in Britain

On May 1900, although Soseki was still working for 5th Higher School, he was ordered to study in Britain for 2 years.

I was ordered to study in Britain in 1900 when I was still working for 5th Higher School as the professor. [...] I was not eager to go Western coutries, but as I have no reason to refuse the order firmly I follow the order.

(Introduction of Bungaku ron (means in English the theory of what the definition of literature is)üEüE/p>

On September 1900 Soseki left the port of Yokohama via Paris for Britain, and arrived at Britain on 28 October.

Soseki went to the University of London and attended some classes, and also took the private lessons of the Shakespearean scholar WJ Craig. Yet, he stopped attending the classes of the university after several months.

I ran to the university and attended the class of the contemporary literary history. Also, I found the private teacher and enabled myself to always ask him any questions I encountered during my study.

I stopped attending the class 3 or 4 months later because I realized that there I could not satisfiy my expected interests nor acquire knowledge. I remembered that I went to take the lessons of the private teacher for almost one year.

Soseki, during his study abroad, decided to read the famous books whose title he knew but which he had not read yet. However, 1 year after his decision he was astonished at what few books he finished reading.

I regretted that I had not had enough time to be absorbed in reading so that at that time I did read only 3 or 4 out of 10 novels which were famous and which I knew only by name. Taking advantage of this opportunity, I decided to read these books as many as I could. Thus one year passed, and I was amazed at what few books I finished reading in contrast with the number of books I decided to read. I realized that spending another year on reading novels meant wasting my time.

Soseki also suffered the great difference between the classical Chinese notion of literature, which he had been familiar with since he was young, and the western notion of literature.

When I was young I preferably learned Chinese classics. Although I stopped learning it soon, my definition of literature was based on 4 Chinese old history books (Zuo-zhuan, Guo-yu, Shi-ji: The Records of the Grand Historian, Han-shu). I naively assumed that the English definition of literature was the same, and thus I thought that I would not regret devoting my life to studying the English Literature. For this innocent and simple reason, I chose the department of English literature. [...]

When I graduated from the university, I felt deceived by the English Literature. [...]

I can appreciate Chinese classics, although my competence of them is not so high. My competence in English was not very high but it was at least as high as the competence in classical Chinese. The reason why I liked Chinese definition of literature and did not like English one was that both definition were quite different from each other. In other words, we cannot assume that the Chinese definition of literature and English one are not the same at all.

Several years after I graduated, under the lonely lamp of the far London, I finally realized this fundamental difference. [...] There in London I determined to conclude the question: what Literature fundamentally is.

Soseki, who "determined to conclude the question", retired to his lodging in London and was absorbed in making notes with very small characters, whose size was the head of the flys.

I kept retiring to my lodging. I put the books about literature away into my bags. This was because I believed that understanding what literature is by reading literary books is like washing the blood with blood. [...]

I devoted my whole time to trying to collect the materials, and spend my whole money on buying the reference books. These 6 or 7 months are the period, during which I made every effort to keep studying most ardently and seriously in my life. [...]

I made as many efforts as I could to read the books I bought, wrote down the comments on the books, and when necessary I made notes. At first the meaning of literature was ambiguous, but 5 or 6 months after I sensed that the meaning was beginning to form within myself. [...]

During my stay in London I wrote the small characters on the notes, and if I piled the notes, the height was 15-8 centi meters. I came back to Japan with these notes as the only product of my study in London.

The last part of the introduction of Bungaku ron, Soseki concluded his study in London:

These two years in London are the most unpleasant period in my life. I lead a miserable life among the British people like a shaggy dog among the wolves. [...]

The British people told me that I was suffering nervous breakdown. I heard that some Japanese person sent a letter to Japan and told the people that I got mad. [...]

After I came back, I was still treated as the mad person who had nervous breakdown. Even my relatives seemed to acknowledge this. As my relatives admitted my madness, I realized that I could not convince people of my soundness. Yet, because of this madness and nervous breakdown, I could wrote "I am a cat.", "Yokyo-shu", and "Uzura-kago", so it is natural that I thank for my desease.

Letters to Kyoko, his wife

Living in London far away from his home, Soseki often sent letters to his wife Kyoko, and was waiting for her replies. In his letter to Kyoshi Takahama dated on 23rd February 1901(Meiji 34), Soseki wrote that 'Waga imoko wo yume miru haru no yo to narinu / I dreamed of my dear wife on one spring night.' Yet Kyoko, a poor correspondent, hardly replied to him.

Though I have a wish to write, . . . I cannot find time when I actually try to do so. Then, as he seems to have been waiting to hear from us, he writes to us, saying that we hardly write him, and that no matter how busy we are, we could have time to write at least one letter to him. . . .

There he seemd to have minded what he had not cared so much here, and he often mentioned about some bold spots of my head and my crooked teeth in his every first letter. You should not have your hair arranged in a Japanese chignon lest it should widen your bold spots, and you had better put on some balm. And finally, he wrote about my bold spots even in I am a Cat. He seems to have minded it considerably. (From The memory of Soseki / Soseki no omoide)

ŃĆĆ

Kyoko, at this time, was in a hard condition as she had to sustain her life with two small children with little money, and Jyuichi Nakane, her father, resigned from the government position and also failed in the market.

After two years when Natume returned from England, life was so miserable. We had no sufficient clothes as we had almost worn out what we had. As to my own clothes, I could handle them. Yet in the case of my children's, I was at a loss: I had to buy some at each season, for they had really nothing, even the used ones.

(From The Memory of Soseki)

As to the letters Kyoko wrote to Soseki, we have the following one written in 1901 (Meiji 34). (Kunihiko Nakajima, 'Spring 1901, Dear my husband in abroad.' New documents: Letters from Kyoko to Soseki in abroad) This was her reply to Soseki's letter dated on 20th February 1901, in which he wrote: 'As time passes, I come to think of Japan more. Even I, such a coldhearted person, dearly miss you. At least I want you to admire it, considering it as something praiseworthy.'

I was surprised as you hardly tell us that you long for home or that you miss your wife. And yet, I am sure that I can surpass you in this respect that I also continuously miss you a lot. On the first night when you left, I started thinking of you so much that I could not sleep well again. At that time, I thought that this loneliness was naturally going to be weakened as days passed. Yet the fact is, the more time passes, the more I think of you. I did not mention this to you as I thought it must be only I who felt in this way. So, I am very happy and pleased if you also remember me in the same way. It is my heart that unites our hearts. . . .

I suppose you have looked at the photographs that I sent to you. Please tear this letter when you finish reading it. On the night of 12th April. Kyoko. Dear Kinnosuke

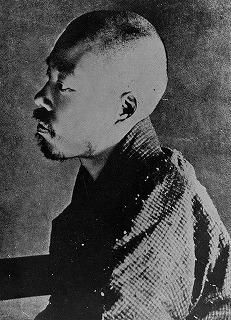

Shiki in his sickbed

Negishi, the place where Shiki was to end his life, was called as 'Village of Kuretake at Negishi' or 'Village of Hatsune,' and it was famous for 'Bamboos' and 'Japanese bush warblers.' It was a quiet and refined place where many artists used to live. In Edo-period, Hoichi Sakai, a painter and poet, Shigemasa Kitao, a Japanese Ukiyoe painter, and Seiken Terakado and Hosai Kameda, Confucians, lived there, and they supported the Edo culture. In the Meiji 20s, Rohan Koda, Koson Aeba and Shiken Morita, who were called as 'the Negishi party' or 'the Negishi school,' were active in their creative activity around this place. The Negishi party is understood as a 'salon' for artists rather than as a literary party. Tenshin Okakura, a leader of artists, and Ogai Mori, when newly married, also lived around Negishi, and they are said to have contacts with the member of the Negishi party.

Shiki composed a lot of Haiku about Negishi and its surrounding area. 'Negishi nite ume naki yado to tazune koyo,' 'Tsuki no Negishi, yami no Yanaka ya wakare michi,' 'Imosaka mo dango mo tsuki no yukari kana,' 'Shoji akeyo Ueno no yuki wo hitome min,' 'Hito mo konu Negishi no okuyo fuyugomori,''Fuyugomoru hito no ohsa yo Kaminegishi.'

Negishi and its neighborhood are also mentioned several times in the works of Soseki. For instance, I am a Cat has the following conversation between Mr. Kushami and Sanpei Tatara.

ŃĆĆ

Shall we have some pudding at Imosaka? Have you tried the pudding there? Madam, why don't you go and try them? They are very soft and inexpensive. You can also have some sake.

(I am a Cat)

In Kokoro, 'I' hear 'Sensei' tell him that 'Yet, you, love is a sin. Do you understand it?' This is while they are 'walking with an easy pace towards the direction of Uguisudani from the back of a museum' after 'going to Ueno together' 'one day at the season of flowers.'

It was since Meiji 25 that Shiki started living at Negishi. Introduced by Katsunan Kuga, a president of Nihon newspaper company, Shiki lived at 88 Banchi with his mother and sister from Matsuyama, his hometown. After Meiji 27, he moved to 82 Banchi, the next to Katsunan Kuga. This is so called 'Shiki-an (Shiki hermitage).' Shiki is said to tell Fusetsu Nakamura as follows: 'For men of letters and artists there is no other places better than Negishi. I will not leave this place. It is quiet and favorable for studies. I will stay here until my last day and I will come to the dust of Negishi.' (Katsuji Wada, Fusetsu and Shiki)

Around the area of Negishi also lived those who were related to Shiki. They are Kyoshi Takahama, Hekigoto Kawahigashi, Fusetsu Nakamura, Chu Asai and Sokotsu Samukawa.

In Kaminegishi there are two alleys which bear the name of animals.

They are Tanuki-yokocho (a racoon dog alley) and Uguisu-yokocho (a Japanese bush warbler alley). I wonder what kind of allays these are.

Out of the Tanuki-yokocho, here comes a gate to the second house of Marquess Maeda. If you go about 36 meters further to the opposite direction of Uguisu-yokocho following the black boarding which is almost 2 meters high, you will come to the back gate of this house. This back gate has various kinds of doorplates, about 14-15. All of these are for the names of the habitants, who live in houses built within the land of Maeda. And if you turn left following this black board and go a little further for another 36 meters, you come to the other alley at which you have to turn left again. On the left side of the alley, you have the same black board, and on the right side, fences of bamboos. There, you have one notice board which has the words of 'Uguisu-yokocho' written in the manner of Oie-ryu (Oie style).

From this notice board if you go 55 meters further and turn, you come to a solitary alley, Uguisu-yokocho. . . .

It is originally a narrow alley, and yet several kinds of branches such as Hinoki, Muku and Hazel forth from the high boarding and the fences of bamboo. This makes us feel that the alley is narrower all the more. In spring, Uguisu (Japanese bush warblers) often alight on these trees and sing. It is said that this is how the alley came to be called as Uguisu-yokocho. In winter time like now, sparrows and greater sand plovers still often come, and you can catch 4-5 of them every day in the trap set on the tall Muku tree. . . .

Those who call upon Shiki's house for the first time and come to this Uguisu-alley with the feeling of good old days, are to see the things above. And they look at each doorplate which belongs to the three houses, and finally they find the one of 'Shiki Masaoka.' When you gladly push at the door of the gate, the doorbell rings, and you are to hear the master coughing even before the sliding paper front doors are open.

(Kyoshi Takahama, Articles on Negishi-Soro: Negishi Soro Kiji)

Many artists gathered at Shiki-an, and they had a lot of literary activities setting Shiki at its centre. 'Shiki in his sickbed was the core of mutual creation' ( Toshinori Tsubouchi, Shiki Masaoka: The Nature of Mutual Creation' (Sozo no Kyodosei)). Shiki, who particularly aimed at the innovation of Tanka, held a first poetry meeting in Meiji 31, and Kyoshi Takahama, Hekigoto Kawahigashi, and others joined it.

Shiki serialized 'A drop of Indian ink' (Bokujyu-itteki) in Japan newspaper from January to July 1901 (Meiji 34), and from September he started writing Gyoga-manroku (Rambling memoir while lying on my back), his memorandum in his sickbed. Moreover, he started another serialization of Byojyo roku-shaku (The sickbed of roku-shaku) in Japan newspaper from May 1902 (Meiji 35). In the first serial, he wrote: 'The sickbed of Roku-shaku(180cms), this is my world. And yet this Roku-shaku is still too spacious for me.' This serialization continued until just before the day of his death. For Shiki, that his writings were appearing in newspapers and magazines was nothing but the proof of his life.

Dear Sir, my life now is in 'The sickbed of Roku-shaku.' Rising up is so hard as if dying every morning. Yet when I open the newspaper and find 'the sickbed of Roku-shaku,' I feel I could slightly revive. How hard it was this morning when I opened the newspaper! There was no 'The sickbed of Roku-shaku,' and I started crying. I cannot stand it.

('A letter to Kazuo Kojima on 20th May Meiji 35')

Since his childhood, Shiki loved little flowers above all things. 'Flowers are my world and my life. From my childhood till now, the pleasure that accompanies wild flowers sometimes makes me feel as if I were God.' ('My sense of beauty as a child': Waga yoji no bikan) For Shiki, who was unable to rise up because of his illness, 'the small garden' at Shiki-an became 'his heaven and earth and the only material for poetry.'

I have a small garden of 66ŃÄĪ. It is in the south of my house, and Japanese Ueno cedar trees are the outside of the fences. As houses of the outskirts of a city are built sparsely, I can see the blue sky spreading over the garden, clouds floating and birds flying so richly. . . .

Last spring, it was I remember a little after the equinoctial week, I planted some packs of seeds that Doctor Ogai sent to me. And yet there was nothing coming out except zinnia plants. I specially wanted to have some amaranthus, and I found it rather disappointing. Yet last summer, there was something that put forth some mysterious buds. As this was the place where I sowed the seeds of amaranthus, I was sure that it must be them, and I cherished them up carefully, setting up a bamboo as a support post. Then, they revealed the colour of red among their seed leaves.

('Memoir of the Little Garden': Shoen no Ki)

On the morning of 14th September Meiji 35, only a few days before his death, Shiki told as follows: 'Since I became sick, I have never ever looked at the garden so quietly in such a peaceful state of mind as this morning.' He dictated the following sentences about the scene of Shiki-an to Kyoshi.

This morning, I woke up in a mosquito net. I was still half in a dream, and yet I made my people get up, calling them. Both my sister, who was sleeping in the next room, and Kyoshi, who was in the guest room, replied to me and came to me at once. . . . When I got up this morning, it was still the same as yesterday that I could not move my legs. Yet my mind was considerably peaceful, perhaps because I happened to have a sound sleep with almost no interruptions last night. My face pointed to the south, and I even could not manage to change its position at all. Keeping exactly the same posture, I looked at outside through the glass of Shoji (the Japanese sliding door). It is a little past six, and the hazy sky with no wind presents an extremely quiet view. In front of a window, there is a bamboo shelf about 3 meters high, which is covered by three reed blinds. Of all the sponge cucumbers that tried to grow up from the eastern side of the shelf, ten of them have already become weak, and none has reached to the top of the shelf yet. As to the flowers, only a few are blooming. In its front, patrinia flowers bloom the highest, and five or six cockscombs are there a little lower than that. Begonia grandis shows its stem still keeping its vigor. Since I became sick, I have never ever looked at the garden so quietly in such a peaceful state of mind as this morning. I gargle my throat. I talk to Kyoshi. At the house in the south, someone seems to start practicing to read books with his voice of about the second year of primary school. . . . While looking at outside with Kyoshi, remembering and talking about one morning when I was at Suma, I sometimes see one or two leaves of the sponge cucumbers flutter as if dewdrops dripped on them. At each time, I felt the coolness of autumn sink into my body, and it was such a pleasant feeling. As I found it rather strange that I felt no sickness at all perhaps due to the too extreme pain, I got to feel that I would like to write something, and I asked Kyoshi to write down what I spelled out.

('On the morning of 14th September')

It was on 19th September 1902(Meiji 35), only a few days after this essay, when Shiki died. 'On the morning of 14th September' was on Hototogisu published on the following day of his death (v.5, no.11). When his mother looked into Shiki's room 'noticing that it was too quiet, he had already breathed his last.' (Kyoshi Takahama, Retrospection of Shiki: Shiki-Koji tsuikaidan) It was about one o'clock in the morning when 'a little waning moon of the seventeenth nights of the lunar calendar hang in the sky brightly.' Shiki was 35 years old.

Shiki left the following three haiku as his final work: 'Hechima saite tan no tsumarishi Hotoke kana,' 'Tan itto hechima no mizu mo maniawazu,' 'Ototoi no hechima no mizu mo torazariki.'

The last photo of Shiki (December Meiji 35)

The death of Shiki and Soseki

On leaving Japan for England, Soseki is understood to have already expected Shiki's death as he wrote

to Kyoshi later that he 'was not to meet Shiki once again while Shiki was still alive.'

(A letter to Kyoshi on 1st December Meiji 35)

'In order to console Shiki in his sickbed,' Soseki sent 'long letters to Shiki several times, describing his own life here and there.' These are the ones of on 9th, 20th and 26th April 1901 (Meiji 34). These letters in which Soseki wrote several episodes of life in London with some unique sense of humour pleased Shiki extremely. Shiki made them entitled 'News from London: London Shosoku,' and they appeared in Hototogisu.

(Hototogisu, v.4, no.8-9)

Shiki wrote his reply to Soseki in his letter on 6th November 1901 (Meiji 34): 'If you can, can you please send me another one while I am still alive?' This was the last letter from Shiki to Soseki.

I am done for. I am crying every day though I have no reason to do so. So, I am not writing to newspapers or magazines any more. I quitted all the letter writing. This is why I have not written you anything for so long. This evening, I got to feel to write you suddenly, and thus I am writing now. The letter that you sent me the other day was extremely good. It was the only thing that made me feel so pleased in these days. You know that I have long wanted to see Europe. And then, I became sick in this way, which makes me feel so pity and miserable. Yet your letter pleased me a lot, for it made me feel as if I went to Europe. If you can, can you please send me another one while I am still alive? (though I know this is a difficult request.) . . .

I feel I am probably not to meet you once again. Or only if we can, I would not be able to talk to you. To be honest, I find it so hard just to live. In my diary, there is a page where the phrase of "Kohaku tell me to come here." are specially written. *

I have lots of things that I want to write you, and yet please do forgive me. I am suffering.

*Kohaku (Kohaku Fujino) is Shiki's cousin who commit suicide by gun in the past.

Yet Soseki could not send another 'News from London' to Shiki. Confining himself in his lodging, Soseki had been struggling with 'the question of what literature in a fundamental respect is' so seriously as to become suffering from 'the nervous breakdown and insanity.' Not being able to satisfy Shiki's wish, Soseki must have felt the strong sense of regret. After his return, Soseki wrote on 'A journal of a bicycle' (Jitensha Nikki), an episode of his practice in riding bicycle. (Hototogisu v.6, no.10) This could be his 'another one' to Shiki, which Soseki could not manage to send.

Toyotaka Komiya, pointing out that it was Shiki who introduced Soseki Nastume, a novelist, writes as follows:

Pressed by Shiki, Soseki wrote 'News from London' in Hototogisu. When Soseki returned from London, Shiki had already died. Yet Kyoshi Takahama, who undertook the work of 'Cuckoo' as a successor to Shiki at that time, encouraged Soseki and made him write 'A journal of a bicycle' (Jitensha Nikki), 'A shield of illusion' (Genei no tate) and 'Botchan'. Quitting his teaching, Soseki became a novelist. . . . It is not too much to say that Shiki was en essentialcharacter for us to have Soseki as a writer. Of course even without Shiki, Soseki would have shown his talent, inspired by some other ways. Yet if Soseki had not had any contacts with Shiki, Soseki might have spent his life only as a scholar. In this respect, their companionship can be understood as something destined.

(Toyotaka Komiya, 'A commentary on Bokusetsu-roku' (Bokusetsu-roku kaisetsu))

Time of Composition I

Soseki returned from England in January 1903(Meiji 35). In April of the same year, he took a position of English teacher as a part-time employee of the First Higher School and another as an English lecturer of Tokyo Imperial University.

On 22nd May 1903(Meiji 35), the First Higher School had the affair of 'Kegon Waterfall,' in which Misao Fujimura committed suicide by throwing himself into the towering waterfall in Nikko. As Soseki once rebuked Fujimura for not having done his homework, he seemed to consider the reason of his pupil's death as his scolding the student.

At Tokyo Imperial University, Soseki lectured 'the View of English Literature.' He was very strict about language and his way of thinking was theoretical. His lectures, therefore, gave the totally different impression to the students who had got used to the way that Lafcadio Hearn (Yakumo Koizumi), Soseki's predecessor, taught based on his passion. Kenji Kaneko, one of Soseki's students, retraces Soseki's teaching as follows:

Mr. Soseki's lectures especially focused on the analytical study of literary criticism which was supposed to be essential when understanding literature itself. His standpoint, therefore, differed a lot from the view of Mr. Hearn, who tried to understand literature not theoretically but rather instinctively.

(Kenji Kaneko Soseki as a human being: Ningen Soseki)

Soseki's lecture on Macbeth, however, was 'with a large attendances' (Kenji Kaneko, Nigen Soseki) as Shakespeare's plays were performed and had a high popularity at that time.

After his return, Soseki continuously suffered from his unstable mental condition. According to his wife Kyoko, these uneasy days lasted from June 1903 (Meiji 36) to May 1904 (Meiji 37). Kyoko remembers these days as follows:

From the rainy season he rapidly became crazy, and since July he has become all the more so. At night, though I could not see any reason for it, he suddenly lost his temper and threw his pillow or anything his hand touched at random. Saying that children cried, he got angry. And sometimes, not knowing what he was doing, he got mad and took his frustration out on anything around himself. We really do not know how to do with him.

(The memory of Soseki, Soseki no Omoide)

I am a cat was composed in Soseki's uneasy days like this. The first part of the novel appeared in Hototogisu v.8, no.4 published in January 1905 (Meiji 38). Soseki originally intended to finish it with only one time. Yet, having the strong response from the reader, it lasted till the tenth and appeared in the same magazine intermittently. In Meiji 38, the first part of I am a cat was published. Fusetsu Nakamura, a painter just returning from his study in France, draw the illustrations for it.

As to I am a cat, Soseki expresses him opinion as follows:

As an old friend of Shiki Masaoka, I wrote him the details of my difficulties at my lodging in London. Then, he made it appeared in Hototogisu. Though I was originally concerned with this magazine, this was the opportunity that had Kyoshi, its editor, ask me to write something when I returned to Japan (Shiki had already died). This is how I wrote I am a cat. On reading my work, however, Kyoshi said that this would not be good enough. When I asked the reasons, there were several of them. I can remember none of them now, but I found them reasonable. So I rewrote it. This time Kyoshi praised my revised work a lot, and he carried it in Hototogisu. My intention, however, was to complete it with only this part. Yet Kyoshi encouraged me to continue it, and it came to be that long while I kept on writing it little by little. This was how things went. I happened to write it, and I had no thoughts at all towards the literary world at that time. I wrote it because I wanted, and I composed it because I wanted. In other words, I myself was in the right time to write it.

(The time was with me: Jiki ga kite itanda--The reminiscent talk on his first work)

Mr. Tofu and Mr. Kushami, they all say what they want to say. Therefore, they are the people of the time of peace. Yet their principle cannot be applied to this present real world. Your contrary opinion is reasonable. Mr. Soseki is also against it. . . .

All what they say is true. And yet it is just a part of the truth. It does not stand for the author's whole view of life at all. I wish you to understand it. The whole of the work itself is a satire. Considering that that sort of satire is perfectly proper to the present day, I represented it in the story of the cat. Yet, if I write a paper on my individual thoughts, I would like to discuss the pros and cons.

(A letter to Kaishu Kuroyanagi on 7th August Meiji 39)

As to I am a cat, I did not have any intention to write so long like that, or any other ideas. I was just to complete it with one writing. I did not expect at all that the work was to gain such strong popularity, either. In the beginning Kyoshi asked me to 'write something,' and I wrote it for him. There was a society of the study of writing at that time, and when I submitted my work to the meeting, I heard that it received such a praise from the people there. . . .

Strangely enough, when I completed my work, I felt I had nothing to write any more. It seemed like I had already discharged all the thoughts in my mind. Yet in ten days or in twenty days, as time passed, I found that there were still something in daily life that I would like to write more about. I can also collect materials for it. This is how I am, and I can make works such as I am a cat long just as much as I want.

(A story on literature: Bungaku dan)

On the other hand, Kyoshi, who recommended Soseki to write something in Hototogisu, looks back the situation in a following way:

In those days, we had a strong passion for writing. We gathered almost every month and had the meeting. This had already existed when Shiki-koji was still alive, and we called it Yama-kai (a party of the climax) following Shiki's belief that 'every writing has to have a climax.' . . . And finally I made a promise with Soseki to call him upon his house on the way to Shiki-an, asking him to try to write something till then as we were supposed to have the Yama-kai on certain day of this coming December. . . .

This work of I am a cat' - - Soseki, when I visited him, had not decided its title yet, keeping the space before the beginning of the work still blank. He said that he was indecisive whether he should name it 'Neko-den' or use 'I am a cat,' the exact sentence with which the novel started, as its title. I agreed to the latter. - - made all our members praise it for only one point that this was 'anyway really unusual.' Then, we made it appear in the opening page of Hototogisu published in January Meiji 38. It is still fresh in our memory that this work made the name of Soseki so well known among the literary world all at once.

(Kyoshi Takahama, Mr Soseki and I (Soseki-shi to Watashi))

From 1905 (Meiji 38) to 1906 (Meiji 39), Soseki wrote his works one after another. These are 'The Tower of London (London To),' 'The Carlyle Museum,(Carlyle Hakubustukan)''Gen-ei no Tate,' 'Koto no Sorane,''Ichiya,''Kairo-kou,' 'Bocchan,' and 'Kusamakura.'

Bocchan in Bocchan is a lovable character up to some point, and we have sympathy for him. Yet if you understand that the person like him has difficulties to adjust himself to the present complicated society because he is too simple and his experience is too poor, it is fair enough: the author's view of life is to be shared with the reader.

(A story on literature: Bungaku dan)

To live simply and purely, that is to say, to live poetically, amounts to only a little part of the meaning of the whole life. Therefore, characters like the hero of Kusamakura cannot go well. He is fine, and yet we have to take the Ibsenian way in order to survive and persist our own belief in this present world.

('A letter to Miekichi Suzuki on 26th October Meiji 39')

I wrote 'Kusamakura' in a way opposite from how general novels are. It is enough if one sense, only a sense of beauty, is to remain in the mind of the reader. I have no other intention apart from this. This is why the story has neither plots nor developments of events.

(A talk on 'My Kusamakura' : Danwa, Yoga Kusamakura)

As to Soseki in this time of composition, Kyoko, his wife, talks as follows:

Though he had no intention to write novels by profession, he had long suppressed his feeling that he would like to write something. Therefore, once starting it, he seemed to be able to work on it continuously almost at once. . . . When I watched him write, he seemed to do it so easily, and it was until twelve or one o'clock in the midnight even when he stayed up the latest to work. Usually, after coming back from university, he used to complete it till at around ten in the evening before or after the dinner. . . . While looking at him working, I felt that he was in high spirits as if he could complete his work immediately once he took pen and papers. Therefore, it was far more than to say that he was in the prime of his time of composition. There is no wonder that he had almost no mistakes in his writing.

(The memory of Soseki, Soseki no Omoide)

From 11th October Meiji 39, 'Mokuyou-kai' (The Society of Thursdays) was held by arrangement of 'having the meeting at three o'clock in the afternoon on Thursdays.'(A letter to Denshi Nomura on 7th October Meiji 39)

At Mokuyou-kai, there gathered Toyotaka Komiya, Torahiko Terada, Miekichi Suzuki, Souhei Morita and Jiro Abe. In 1916 (Taisyo 6), Soseki's later years, Kan Kikuchi, Ryunosuke Akutagawa and Masao Kume joined it for the first time.

The day of meeting of Mr. Soseki is on Thursday. It is the usual way that the young, the pupils of Mr. Soseki, gather and have a comfortable chat as they want from the evening. It had been like this for long time, and it still keeps the same. The line-up, however, has been changed a lot. In the beginning, at the time of Sendagi, there joined people like Kyoshi Takahama, Yomota Sakamoto (neither of them are Soseki's pupils), Torahiko Terada and Toyojyo Matsune, who had already hold each of their schools. Then, Miekichi, Toyotaka, Kyusen and Yoshitaro Nakagawa, who teaches Latin at The 8th Higher School, came later.

(Soseki Sanbou Zadan)

Time of Composition II

Soseki, from 1905(Meiji 38) onwards, had been indecisive about whether he should continue to work as a teacher or become a writer. In his letter on 15th July Meiji 38 to Yoshitaro Nakagawa, one of his pupils, Soseki wrote as follows:

The other day Nihon Shinbun(Nihon Newspaper company) came and suggested me to write any kind of things occasinally. That made me think about it considerably -- if I can earn ten yen a day by writing only one article every day, it would be far better to quit the University and be a newspaper-man.

In October Meiji39, after writing Kusamakura, Soseki also sent the following letters to his acquaintances:

I am a man of ambition, who wants to leave my own writing behind me. . . . I hardly want praise from my neighbors. I want the faith of the world. I do not want it. I expect the worship from the people in future generations. Only when I have hope in this, I can feel that I am a great man.

(A letter to Souhei Morita on 21st October Meiji 39)

Till now I had no chance to try my ability to know how great I am. I had never trusted myself. I had just lived my life, depending on my friends' and elders' sympathy and my neighbors' kindness. From now on, I will never ask such things. I will never rely on even my wife or my relatives. I will keep on going alone till the deadend, and I will die there.

(A letter to Kokichi Kano on 23rd October Meiji 39)

ŃĆĆ

Entering into the world of literature on one aspect, I would like to follow literature, on the other, with such a sense of life and death, the strong mind of a knight of the Restoration, in which people did risk their lives. If not, I rather feel that I am only a timid man of letters, who chooses the easier ways escaping from the difficulties, and who favours leisure hating the rush.

(A letter to Miekichi Suzuki on 26th October Meiji 39)

In 1907(Meiji 40), Soseki finally joined the Asahi Shimbun newspaper company. On Soseki's joining Asashi Shimbun newspaper company, Sosen Torii, Sanzan Ikebe and Genji Shibukawa assisted him. After this, all the works of Soseki came to be appeared on Asashi Shimbun.

The fact that a university lecturer got employed by the newspaper company became the talk of the town at that time.

Quitting the job at university and entering Asahi Shimbun, I found people looking at me with surprise. Some of them even asked me the reason of it, and some praised me for making a daring decision. I had never expected that leaving university and becoming the newspaper-man instead was to be such an unusual thing.

If newspaper companies are the business, so is university. If it were not so, there would be no necessity that people want to be professors and doctors. There would be no need to have their monthly payment raised, or to have them appointed as high positions by the government. If newspaper companies are a vulgar occupation, it is exactly the same with university. The difference is only who runs it: one individual or the government.

(On entering Asahi Shinbun : Nyusha no Ji)

From the end of March to April Meiji 40, Soseki traveled around Kyoto and Osaka. Kyoto is the place where he visited with Shiki before.

It was already about fifteen years ago when I came here with Shiki and thought that Zenzai (Sweet Azuki beans) and Kyoto were the same. As the moon was full on one summer evening, we walked around Kiyomizu temple, . . . When we realized that the brass was just brass, we threw our uniform away and jumped into the world as we really were. Spitting blood, Shiki became the newspaper-man, and I drew back into the west as if running away. Each of our life became uncertain. At the end of his uneasiness, Shiki finally came to be in the dust. His bones are now decaying. Shiki would never have expected that I, at the time of his bones decaying, come to be a newspaper-man by quitting the position of a teacher.

(On the evening when I arrived Kyoto: Kyo ni tsukeru yoru ni)

From 23rd June to 29th October Meiji 40, Soseki wrote Gubijinso as his first work on entering Asahi Shimbun newspaper company. Toyotaka Komiya said, 'Mitsukoshi department store offered Gubijinso-Yukata(kimono for the summer), Gyokuhodo launched Gubijinso-rings, and vendors of newspapers at stations sold Asahi Shimbun crying "Soseki's Gubijinso." The society made so much fuss about it.' (Natsume Soseki)

I keep on writing Gubijinso every day. You must not have such sympathy towards the woman like Fujio. That is a disgusting woman. She is poetic, and yet she is not matured. She lacks the sense of morality. Doing away with her at the end is a main theme of this story. If I cannot do this well, I will save her life. Yet if she survives, the person like Fujio comes to degrade herself all the more. At the end of the story, I will make one philosophy clear. This is a theory. I am writing the whole story to explain this. Therefore, you should not consider her good.

üEüEA letter to Toyotaka Komiya on 19th July Meiji 40)

After Gubijinso, Soseki wrote Kofu (1st January to 6th April Meiji 40) and Yumejyuya (25th July to August Meiji 41). Then he continued Sanshiro (1st September to 29th December Meiji 41), Sorekara (27th June to 14th October Meiji 42) and Mon (1st March to 12th June Meiji 43), so called 'the first trilogy.' It is said that the relationship between Sanshiro and Yojiro in Sanshiro especially reflects the friendship of Soseki and Shiki while they were students.

The Title - 'The young man,' 'East and West,' 'Sanshiro,' and 'Heiheichi' -- I would like you to pick up one from these. The one I chose first was Sanshiro. I think Sanshiro the best as it is the commonest. Yet I feel that it does not make us feel that we would like to read the work.

On entering university in Tokyo after graduating from his high school at some country area, Sanshiro experiences something new. As he meets his fellow students, his seniors and young women, his surroundings come to move around him. What I do is just to set these characters in this situation. Then, they start moving as they will, and some evens are to be created on their own.

(A letter to Genji Shibukawa in Meiji 41)

Shiki used to be fond of fruits. He could eat them as much as he liked. Once he ate sixteen big persimmons at one time, and yet he was just fine. I cannot do as Shiki did. - - Sanshiro listens to it smiling. And yet he found only Shiki's talk appealing.

(Sanshiro)

In many respects, it is 'sorekara' (and then). I wrote about university students in Sanshiro, and in this novel I wrote things after. Therefore, it is 'and then.' The hero in Sanshiro is such a simple man as you see, and the new hero is a man after Sanshiro. In this respect as well, it is 'and then.' This hero, at the end of the story, is to fall into his strange fate. We cannot know what is going to happen to his life after that. This is another 'and then.'

(A plan for Sorekara: Sorekara Yokoku)

Thank you for your postcard. From the day when Mon appeared on the newspaper till today, no one has said anything about it to me. These days, I have got used to the situation of solitude, and I can manage to live anyway without having any sympathy of arts. Therefore, I do not expect any praise for my works at all. Yet I feel very happy and content to hear from you that you have read the part of Mon and that it made you touched.

(A letter to Jiro Abe on 12th October Taisho 1)

In 1909 (Meiji 42), Soseki, on the invitation of Zeko Nakamura, traveled around Manchuria and Korea, and he wrote 'Manchuria-Korea here and there' (Mankan tokoro dokoro).

From March to June 1909 (Meiji 42), Soseki wrote Mon in Asahi Shinbun. After the serialization, Soseki was hospitalized for treatment of the stomach ulcer. In August, he went to Shuzenji spa at Izu for a change of climate. Yet from the next day of his arrival his condition became worse, and on 24th August he spit a lot of blood and got into critical condition. This is so called 'A serious condition at Shuzenji: Shuzenji no Taikan.' Calling his own condition of this time 'a death for half an hour: 30pun no shi', Soseki wrote as follows:

Having no doubt at all, I had believed that the 'I,' who forced myself to turn towards the right, and another 'I,' who recognized some flesh blood in a basin at my bedside, were linked each other without any gap. I understood that my consciousness was working properly so as not to have any single hair to be put between these two. Later, when my wife told me that it was not like this at all and that I was dead for half an hour at that time, I was really surprised. . . . To tell the truth, this experience - - I wonder if I can call it the first experience. This experience, which is between one usual experience and another, has such a poor content that it seems not to hinder the link of the two at all - I do not know how I can describe. I even did not have any sense of feeling that I woke up. I also did not think that I came out of the negative to the positive. A faint sound of humming, the sound of something going far away, the smell of the dream of running away, the shadow of the old memory and the remains of the fading impression - - Of course, I did not think that I finally managed to pass the dividing line of the ethereal only after counting almost of all the expressions to describe the mystery of humans. The next moment when I just tried to incline my head on the pillow towards the right as I felt sick, I happened to recognize the blood in the basin. For me, this death for half an hour, which was inserted between these two, is as good as not existing at all as my memory of experience both from the matters of time and space. Listening to my wife's explanation, I thought that death was such a trivial thing. Then, I was deeply touched by the fact that this contrast of life and death, which came upon my mind all of a sudden, was so abrupt and had no relation each other at all.

(Things on my mind: Omoidasu Koto nado)

In February Meiji 44, Soseki received a notice from the Ministry of Education to give him a doctoral degree. However, as Soseki declined this offer, the situation concerning his degree was thrown into confusion.

From the government's point of view, the system of doctoral degrees must be effective as a device to encourage leaning. Yet it is clear that a lot of harmful influences can be brought to our nation when we develop a trait to further all the scholars' leaning only for becoming doctors or when they act based on this kind of extreme tendency. I do not think that we should destroy the system of doctoral degrees itself. Yet if we place such a high value on doctoral degrees as to make people think that only doctors can be the true scholars, leaning itself comes to be under the control of only a few doctors. It then comes to be in the hands of some academics of the nobility, and the other scholars are to be neglected as a result. I am very much anxious about these harmful effects. Because of this reason, I find the Academy in France also unpleasant.

Therefore, it is completely the matter of my principle that I declined the offer of my doctoral degree.

(The consequence of the issue of doctoral degrees: Hakushi Mondai no Nariyuki)

In January 1912 (Meiji 45), Soseki resumed his composition and started writing To the Spring Equinox and Beyond: Higansugimade. On serializing Higansugimade, Soseki told: 'I have to repay readers' favor that they read my work every day as their daily routine.'(On 'To the Spring Equinox and Beyond': Higansugimade ni tsuite)

Higansugimade (To the Spring Equinox and Beyond) is only a simple title. I named it just because I am thinking to write from New Year's Day till the equinoctial week. I have always carried an idea that if I write some short stories and unite them to be one long story, this could be an interesting work for the newspaper novel more than we expect. Yet I had not opportunities to try this, and time has passed until today. If I have abilities enough for this now, I would like to compose Higansugimade as I once wished to do.

(On 'To the Spring Equinox and Beyond': Higansugimade ni tsuite)

After this, Soseki wrote The Wayfarer: Kojin (12th January Taisho 1 to 17th November Taisho 2) and Kokoro (20th April to 11th August Taisho 3), the works so called 'the latter trilogy' with Higansugimade. In 1915 (Taisho 4), he composed Grass on the Wayside: Michikusa (3rd June to 14th September Taisho 4), the work which is supposed to reflect his autobiographical aspects the most. From 5th May Taisho, he serialized Light and Darkness: Meian (26th May to 14th December Taisho 5).

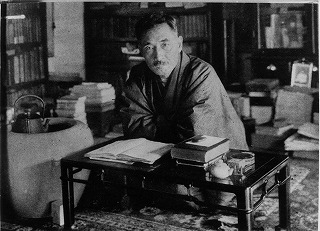

Soseki in Taisho 3 (the time of writing 'Inside the glass door: Garasudo no naka')

I am still writing 'Meian' in the morning. My feelings are based on pain, pleasure and instrumental, these three. I am pleased to find that it is rather cool outside. And yet while keeping on writing such things every day almost already hundred times, I come to feel something vulgar. So, I started creating Chinese poems in the afternoon as my routine a few days ago. It is only one or two poems in a day. And they are composed of eight phrases of seven words. I cannot make then easily. As I give up whenever I do not want, I cannot tell how many I am going to manage to compose.

(A letter to Masao Kume and Ryunosuke Akutagawa on 21st August Taisho 5)

However, at the end of November 1916 (Taisho 5), Soseki's stomach ulcer was aggravated, and he was again taken to his bed. He went to his rest on 9th December, leaving Meian incomplete.

*Photos of Soseki and Shiki in 'The life of Soseki' are from Kanagawa Museum of Modern Literature, Matsuyama City of Shiki Memorial Museum, The Editorial Office of Mitsuo Fujita. All rights reserved.

*This manuscript is a revision of 'Shiki and Soseki' in The Project of Tohoku University Library in 2003: Men of Letters in Meiji and Taisho - Soseki's Acquaintances.